What is meant by the phrase ‘dictatorship of the proletariat’?

The MARX MEMORIAL LIBRARY explains one of Marxism’s most commonly misunderstood concepts

WHAT is the “dictatorship of the proletariat”? In essence, it means “For the many, not the few” — a phrase that has become well-known since last June’s elections.

More and more people are determined to challenge a society where wealth and power are concentrated in the hands of a tiny minority (under 4 per cent) of the UK population.

But “dictatorship” commonly refers to autocratic rule by an individual or clique. Socialists and communists have always fought against dictatorships.

So why did Marx and Engels argue for a “dictatorship of the proletariat” and what did they mean by this?

The phrase doesn’t appear in the Communist Manifesto, written in 1847. It was coined a few years later by the communist journalist Joseph Weydemeyer, using the example of Cromwell’s Commonwealth of the 17th century — the “English revolution” — which abolished much of what still remained of the feudal state and replaced it with the basis for agrarian (and subsequently industrial) capitalism.

Marx’s study of the French revolution (1789-99) and his experience of the defeat of the European “people’s spring” of 1848 convinced him that it isn’t enough to campaign for piecemeal socialist policies which can easily be undermined or reversed within a capitalist state.

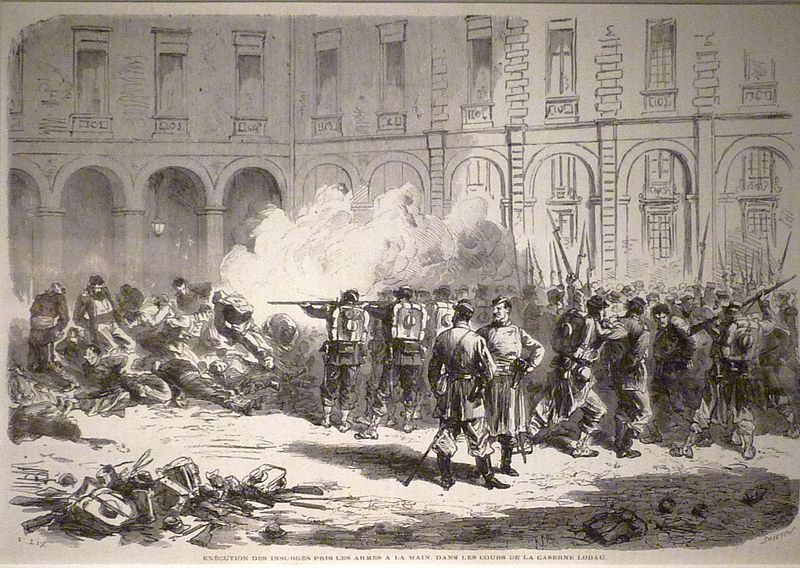

And after the collapse of the Paris Commune in 1871, he argued against those who advocated a gradual transition to socialism as well as against anarchists, who wanted immediately to abolish the state altogether.

He wrote: “Between capitalist and communist society lies a period of revolutionary transformation from one to the other.

“There is a corresponding period of transition in the political sphere and in this period the state can only take the form of a revolutionary dictatorship of the proletariat.”

The term “dictatorship” meant something rather different in Marx’s day from what it does today.

Marx adopted it as a rhetorical device to emphasise the class-biased nature of the state under capitalism and the need within socialism to transform the state to secure an irreversible shift of power in favour of working people, the majority. This would lay the basis for a communist society.

Today, the state, broadly defined, is more complex than it was 150 years ago. Working-class struggles secured important concessions, including a National Health Service, education, pensions and welfare services, housing, water and energy supply, and transport.

All were imperfect, all have been milked by capital as a source of profit, and all today, where not already privatised, are under sustained attack.

Alongside these concessions, the core of the state, including the permanent Civil Service (with its close ties with economic elites), security services, the military, the legal system, banks and the media, still functions to maintain class rule in the interest of capital.

For Marx and Engels, the political, legal and coercive apparatus of the state would disappear within communism — it would “wither away” (something that we’ll look at in another answer).

But this could not happen immediately after a successful revolution while the old ruling class was still in place and counter-revolution remained a real and immediate danger.

In the 1872 edition of the Manifesto, Marx and Engels argued that “the working class cannot simply lay hold of ready-made state machinery, and wield it for its own purposes.” The state itself would need to be transformed.

The past century is littered with examples of the way that socialist administrations throughout the world have been undermined or destroyed by economic sanctions, subversion and direct military intervention.

Venezuela is merely the latest example of a democratically elected socialist government under concerted attack by international capital (led, of course, by the United States).

The television adaptation of MP Chris Mullin’s A Very British Coup presents a compelling fictional scenario of the likely ruling-class response to an elected socialist government in Britain.

The term “proletariat” also needs some dissecting. It’s not quite the same as “working class.” Working classes exist in all class societies, including slavery and feudalism.

Marx and Engels gave the name proletariat to the new working class that emerged with capitalism, composed of workers (“wage labourers”) who lived by selling their labour-power to capitalists who own the means of production, distribution and exchange.

The proletariat were seen as potentially revolutionary because capitalism itself had brought them together — in the workplace and in communities, where they could begin to understand their situation, and organise to change it.

This was contrast to other workers, including the peasantry (still widespread in Europe), as well as to small shopkeepers, independent craftspeople and other “petite bourgeoisie” that they considered largely conservative.

Since then there have been great changes in the composition of the working class, which includes public employees, health workers, teachers, small traders, the self-employed — everyone who works for a living together with their families and dependants (including those unable to work through ill-health or disability).

So a successful socialist programme will need to replace the present “dictatorship” of a tiny ruling class by a state which serves the interests of the vast majority of the population.

A major challenge which needs to be the focus of debate within the left is the form that such a state might take and how it may be achieved.

It will be necessary to learn from the successes, mistakes and failures of existing and former socialist societies. New forms of popular participation, including a democratised parliamentary system based on proportional representation and direct democracy in local communities and in the workplace, will be essential to avoid the dangers of over-centralisation, elitism, careerism and bureaucratic control.

Full accountability of state power to the people will need to be accompanied by free and wide-ranging debate facilitated by accessible and diverse mass media.

Democratic rights and freedoms will become deeply entrenched in every aspect of economic and political life free from the restrictions and distortions imposed by monopoly capital.

As a more recent, British, communist manifesto declares: “Holding state power will enable the working class and its allies to complete the process of removing all economic and political power from the monopoly capitalist class. As capitalism is dismantled, so the construction of a new type of society — socialism — can proceed.”

The Marx Memorial Library’s Trade Unions, Class and Power course with Professor Mary Davis starts on January 30 at 7pm. For further details click here.